JMM Related Content

JMM Related Content

Only StoreLoad Barrier on x86 Architecture

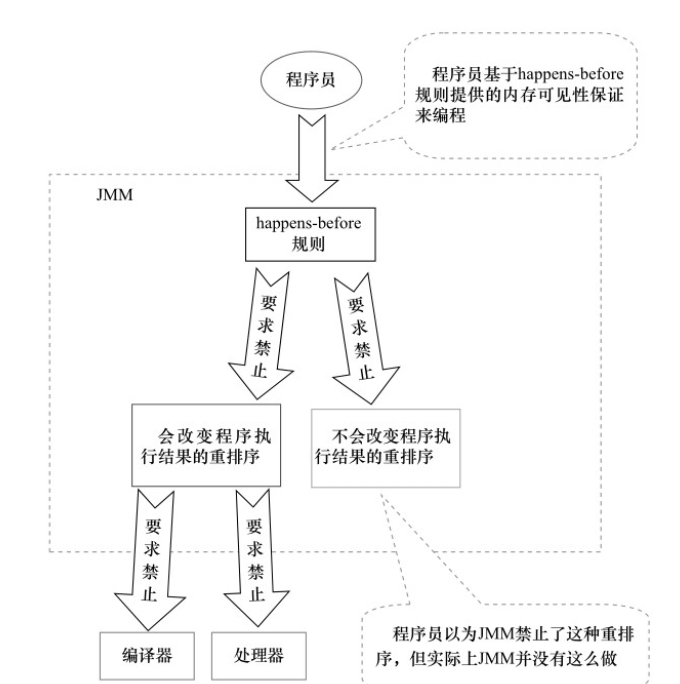

JMM Memory Model Design Principles

For reordering that changes program execution results, JMM requires compilers and processors to prohibit such reordering.

For reordering that does not change program execution results, JMM makes no requirements for compilers and processors (JMM allows such reordering).

Definition of happens-before Relationship

-

If one operation happens-before another operation, then the execution result of the first operation will be visible to the second operation, and the execution order of the first operation is before the second operation.

-

The existence of a happens-before relationship between two operations does not mean that the specific implementation of the Java platform must execute in the order specified by the happens-before relationship. If the execution result after reordering is consistent with the result of execution according to the happens-before relationship, then such reordering is not illegal (that is, JMM allows such reordering).

- 1 above is the JMM's promise to programmers. From a programmer's perspective, the happens-before relationship can be understood as follows: If A happens-before B, then the Java memory model guarantees to the programmer that the result of operation A will be visible to B, and the execution of A is before B. Note that this is just a guarantee made by the Java memory model to programmers!

- 2 above is the constraint principle of JMM on compiler and processor reordering. As mentioned earlier, JMM actually follows a basic principle: As long as the execution result of the program (referring to single-threaded programs and correctly synchronized multi-threaded programs) is not changed, the compiler and processor can optimize however they want. The reason JMM does this is: Programmers do not care whether these two operations are really reordered, programmers care that the semantics during program execution cannot be changed (i.e., the execution result cannot be changed). Therefore, the happens-before relationship is essentially the same thing as as-if-serial semantics.

Similarities and Differences between happens-before and as-if-serial

Similarities:

- The purpose of as-if-serial semantics and happens-before is to increase the parallelism of program execution as much as possible without changing the program execution result.

Differences:

- As-if-serial semantics guarantees that the execution result of the program within a single thread is not changed, and the happens-before relationship guarantees that the execution result of correctly synchronized multi-threaded programs is not changed.

- As-if-serial semantics creates an illusion for programmers writing single-threaded programs: Single-threaded programs are executed in program order. The happens-before relationship creates an illusion for programmers writing correctly synchronized multi-threaded programs: Correctly synchronized multi-threaded programs are executed in the order specified by happens-before.

happens-before Rules

- Program order rule: Each operation in a thread happens-before any subsequent operation in that thread.

- Monitor lock rule: Unlocking a lock happens-before subsequent locking of that lock.

- Volatile variable rule: A write to a volatile field happens-before any subsequent read of that volatile field.

- Transitivity: If A happens-before B, and B happens-before C, then A happens-before C.

- start() rule: If thread A executes operation

ThreadB.start()(start thread B), then thread A'sThreadB.start()operation happens-before any operation in thread B. - join() rule: If thread A executes operation

ThreadB.join()and returns successfully, then any operation in thread B happens-before thread A returns successfully fromThreadB.join()operation.

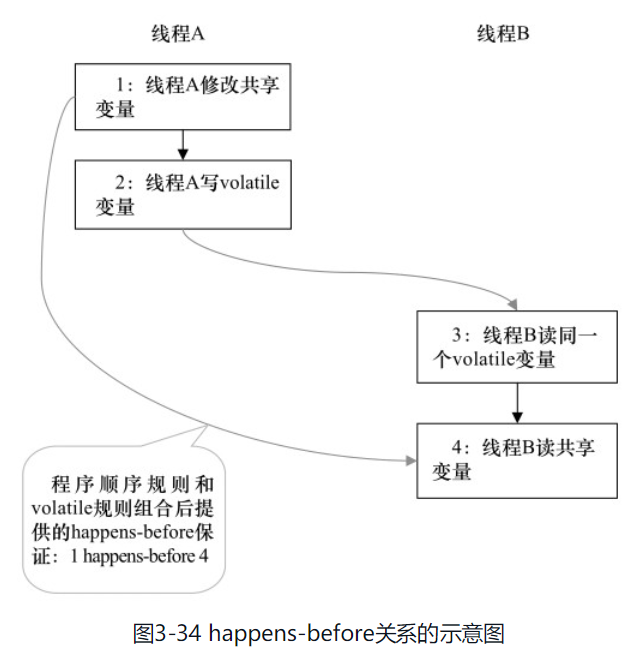

- 1 happens-before 2 and 3 happens-before 4 are generated by the program order rule. Since compilers and processors must comply with as-if-serial semantics, that is, as-if-serial semantics guarantees the program order rule. Therefore, the program order rule can be seen as an "encapsulation" of as-if-serial semantics.

- 2 happens-before 3 is generated by the volatile rule. As mentioned earlier, a read of a volatile variable can always see the last write to this volatile variable (by any thread) before it. Therefore, this feature of volatile can ensure the implementation of the volatile rule.

- 1 happens-before 4 is generated by the transitivity rule. The transitivity here is guaranteed by the memory barrier insertion strategy of volatile and the compiler reordering rules of volatile.

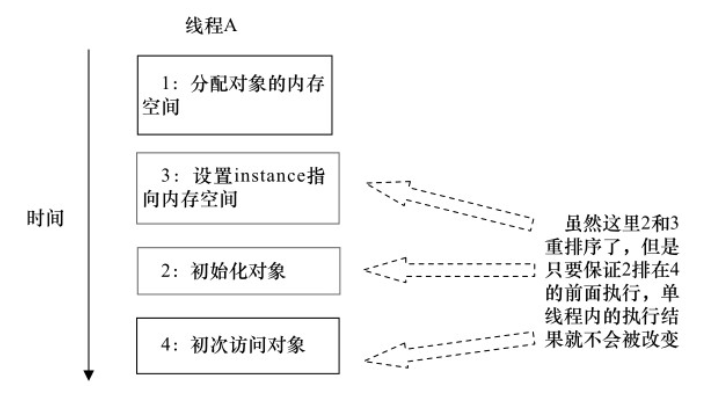

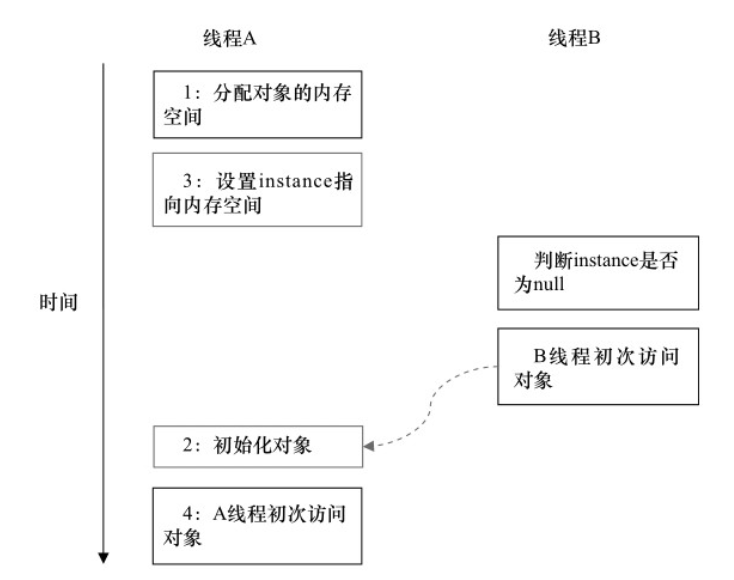

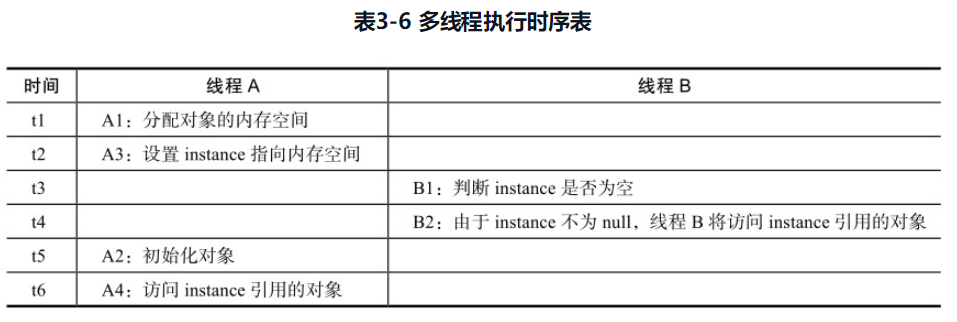

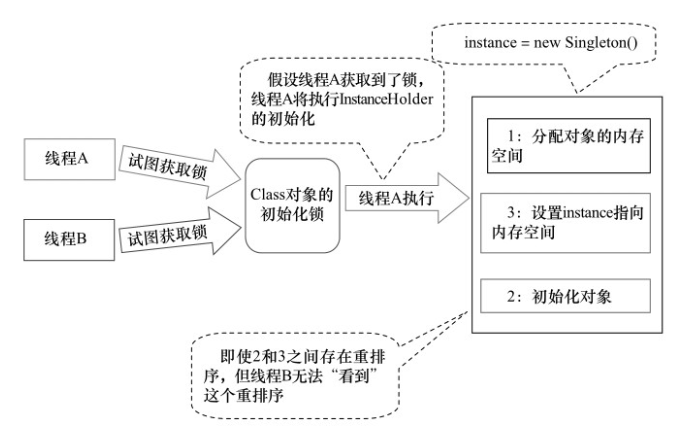

Instruction Reordering May Occur During Multi-thread Concurrent Object Initialization

Although A2 and A3 here are reordered, the intra-thread semantics of the Java memory model will ensure that A2 is executed before A4. Therefore, thread A's intra-thread semantics have not changed, but the reordering of A2 and A3 will cause thread B to determine that instance is not null at B1, and thread B will next access the object referenced by instance. At this time, thread B will access an object that has not yet been initialized.

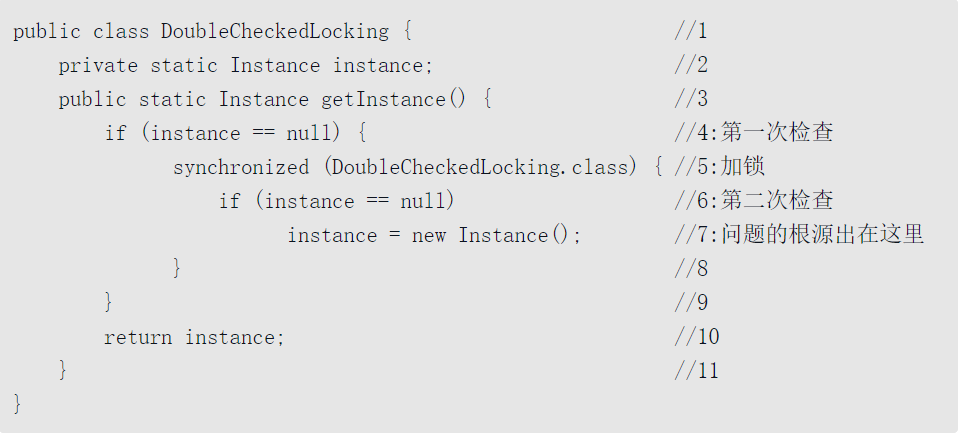

After knowing the root cause of the problem, we can come up with two ways to achieve thread-safe lazy initialization.

- Disallow reordering of 2 and 3.

- Allow reordering of 2 and 3, but disallow other threads from "seeing" this reordering.

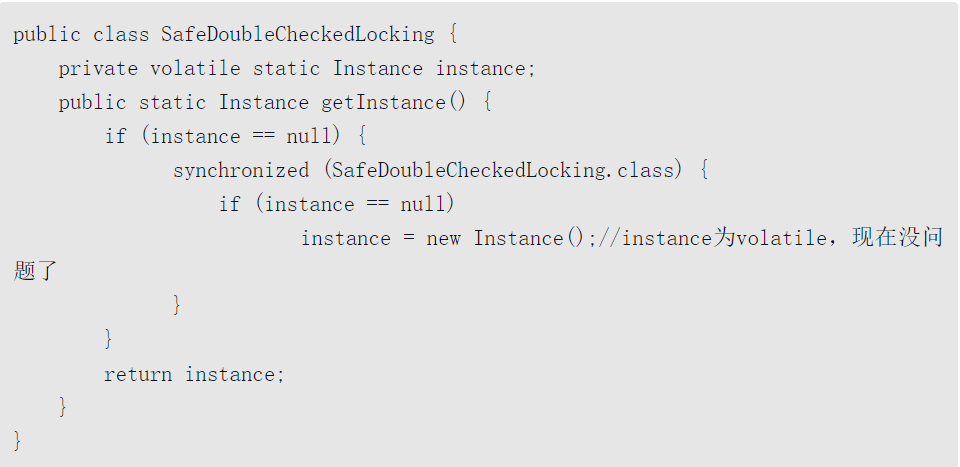

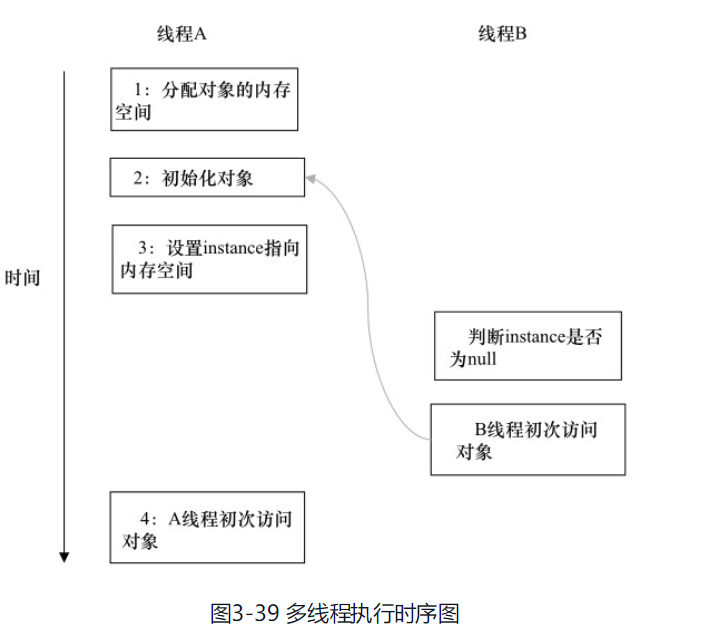

Solution based on volatile

This solution essentially ensures thread-safe lazy initialization by prohibiting reordering between 2 and 3 in Figure 3-39.

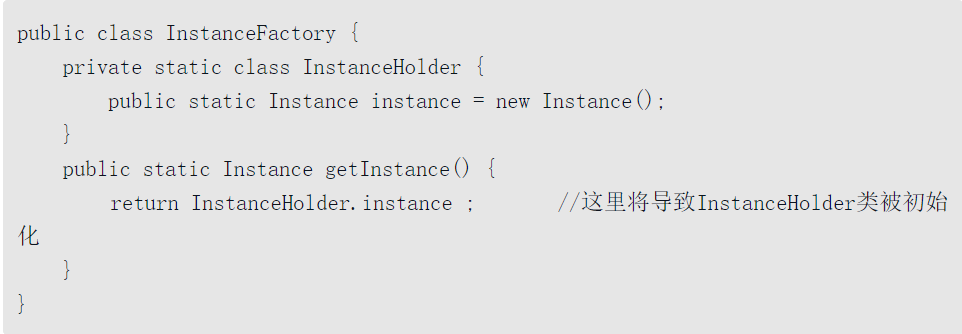

Solution based on class initialization

During class initialization, the JVM acquires a lock. This lock can synchronize the initialization of the same class by multiple threads.

A Class or Interface Type T Will Be Immediately Initialized When Any of the Following Occurs for the First Time

- T is a class, and an instance of type T is created.

- T is a class, and a static method declared in T is called.

- A static field declared in T is assigned.

- A static field declared in T is used, and this field is not a constant field.

- T is a top-level class (Top Level Class, see Java Language Specification §7.6), and an assertion statement is executed nested inside T.

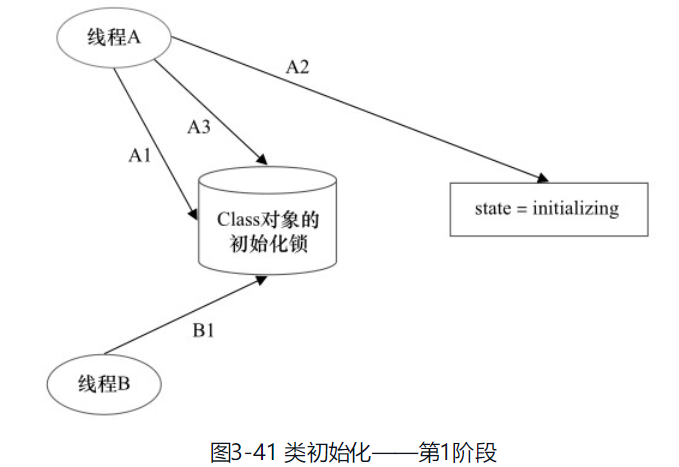

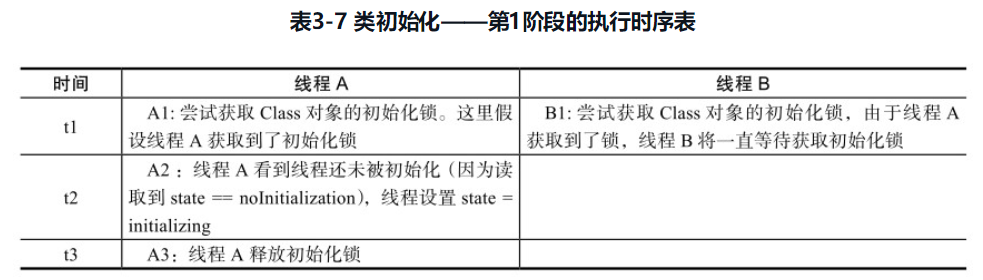

Class Initialization Process

Phase 1: Control class or interface initialization by synchronizing on the Class object (i.e., acquiring the Class object's initialization lock). The thread acquiring the lock will wait until the current thread can acquire this initialization lock.

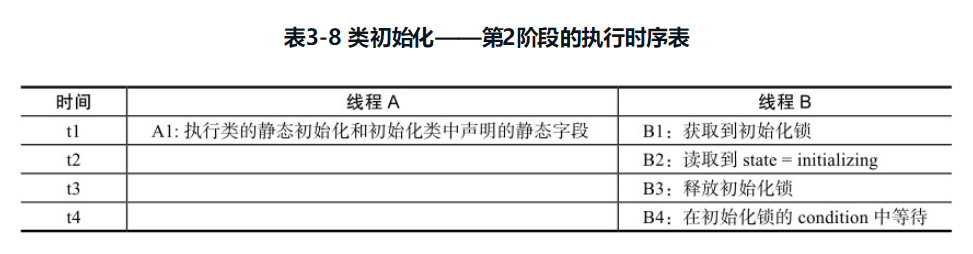

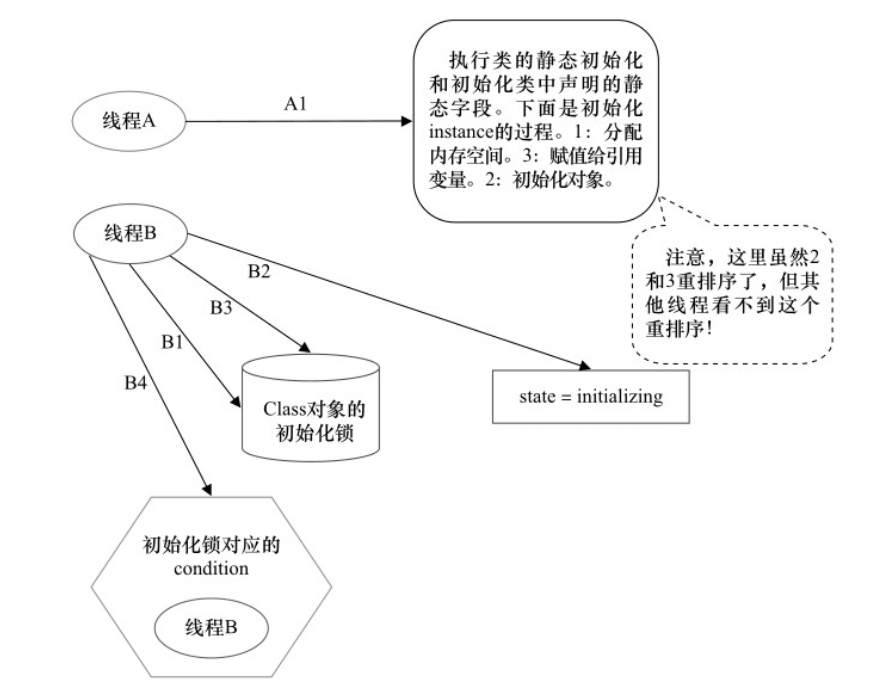

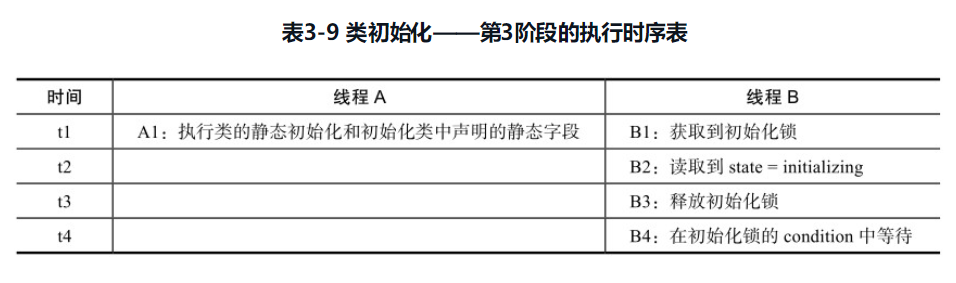

Phase 2: Thread A executes class initialization, while thread B waits on the condition corresponding to the initialization lock.

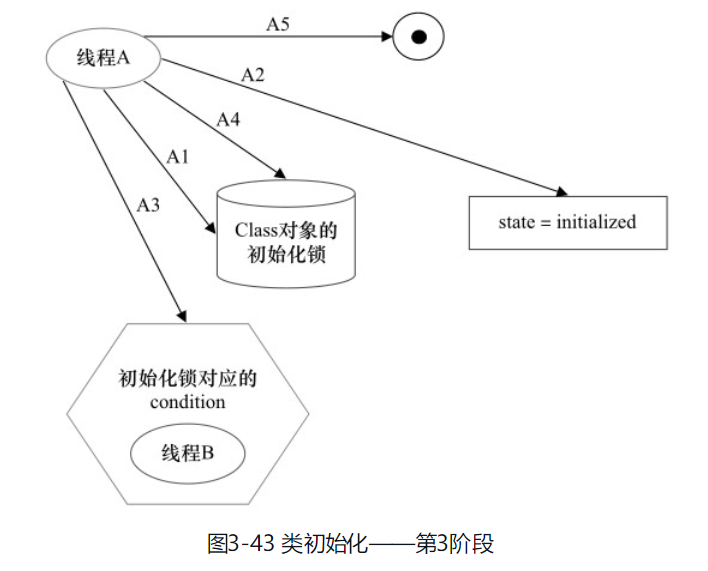

Phase 3: Thread A sets state=initialized, then wakes up all threads waiting in the condition.

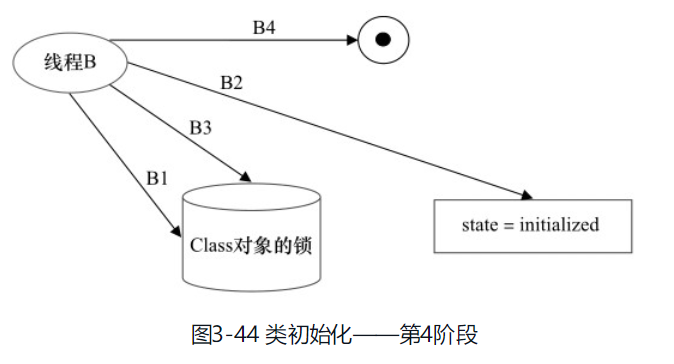

Phase 4: Thread B ends class initialization processing.

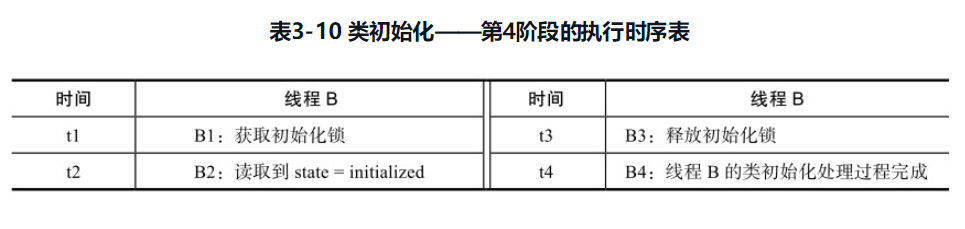

Thread A executes class initialization at A1 in Phase 2 and releases the initialization lock at A4 in Phase 3; Thread B acquires the same initialization lock at B1 in Phase 4 and starts accessing the class only after B4 in Phase 4. According to the lock rules of the Java Memory Model specification, there will be the following happens-before relationship. This happens-before relationship will guarantee: Thread B will definitely see the write operations performed by Thread A during class initialization (executing class static initialization and initializing static fields declared in the class). Phase 5: Thread C executes class initialization processing.

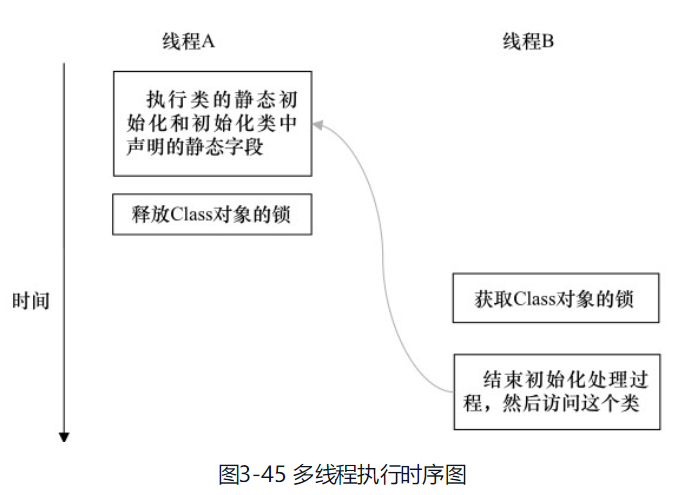

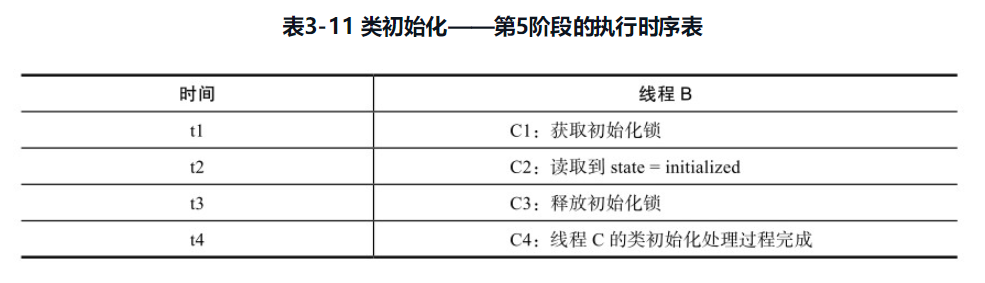

After Phase 3, the class has completed initialization. Therefore, the class initialization processing process of thread C in Phase 5 is relatively simpler (the previous class initialization processing processes of threads A and B both experienced two lock acquisition-lock releases, while thread C's class initialization processing only needs to experience one lock acquisition-lock release). Thread A executes class initialization at A1 in Phase 2 and releases the lock at A4 in Phase 3; Thread C acquires the same lock at C1 in Phase 5 and starts accessing the class only after C4 in Phase 5. According to the lock rules of the Java Memory Model specification, there will be the following happens-before relationship.

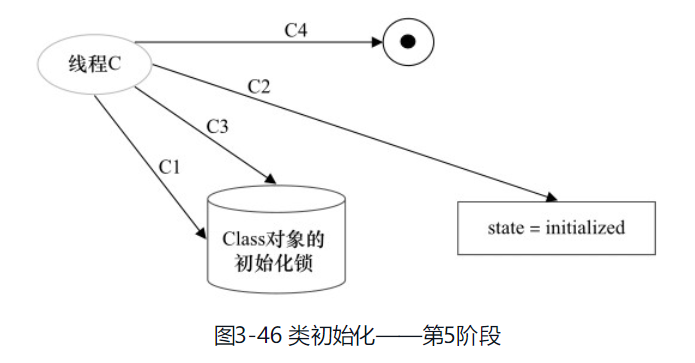

By comparing the double-checked locking solution based on volatile and the solution based on class initialization, we will find that the implementation code of the solution based on class initialization is more concise. But the double-checked locking solution based on volatile has an additional advantage: in addition to implementing lazy initialization for static fields, it can also implement lazy initialization for instance fields.

Field lazy initialization reduces the overhead of initializing classes or creating instances, but increases the overhead of accessing lazily initialized fields. Most of the time, normal initialization is better than lazy initialization. If you really need to use thread-safe lazy initialization for instance fields, please use the solution based on volatile lazy initialization introduced above; if you really need to use thread-safe lazy initialization for static fields, please use the solution based on class initialization introduced above.

Reference Materials

- Book Name: "The Art of Java Concurrency Programming" Authors: Fang Tengfei, Wei Peng, Cheng Xiaoming

- Attribution: Retain the original author's signature and code source information in the original and derivative code.

- Preserve License: Retain the Apache 2.0 license file in the original and derivative code.

- Attribution: Give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made.

- NonCommercial: You may not use the material for commercial purposes. For commercial use, please contact the author.

- ShareAlike: If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original.